Content Warning: The following Webpage showcases primary sources which contain language that, although offensive, is crucial for telling the story of Domestic Servitude in New London, CT. Reader discretion is advised.

The Headstone (above) of Osceola Richardson, a Black and Indigenous Migrant from reconstruction-era Florida who worked as a domestic servant in New London for over fifty years. She was ultimately moved to the poorhouse on Garfield Ave, where she died. Her headstone was purchased by the Eggleston Family, who employed her. Although Richardson was slated to be buried in the Williams family plot, she was ultimately buried in a corner of the Cedar Grove cemetery reserved for Black residents.

Domestic and residential servitude served as a fundamental social relationship for Black migrants and White Immigrants throughout the early twentieth century in New London. For many, particularly for young women, jobs in the domestic sphere represented the only employment opportunities available. At the same time, domestic servitude relied on an intense power imbalance between employing families and domestic labor. In other Northeastern cities such as Boston, families actively sought vulnerable women who were entirely dependent on meager wages from servitude, who they felt made the best servants (Deutsch, 67). Throughout New London’s shifting social landscape in the twentieth century, this manifested in a demographic change from White immigrant labor to Black labor.

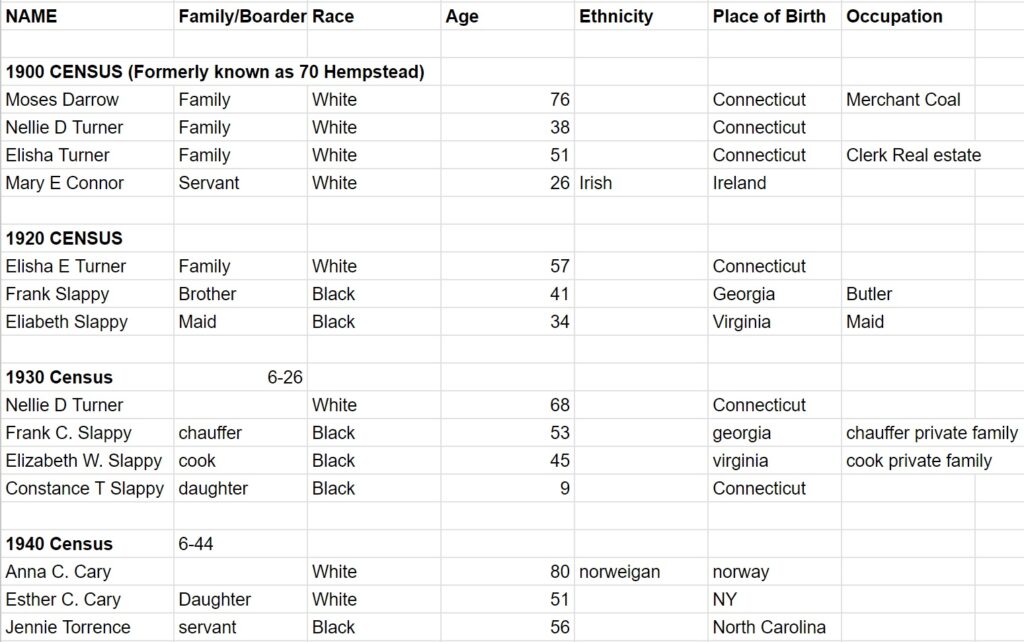

On Hempstead street, north-side families were most likely to hire full time Domestic servants. These families were also almost exclusively white, from the Northeast, and earned their money from professional occupations and property ownership.

Census data for 190 Hempstead, which demonstrates the continuation of Domestic Servitude from 1900-1940. While servant demographics changed considerably over time, the social categories of employing families remained relatively static.

From 1900-1910, Hempstead street had very few Black Live-In servants. Irish and other ethnic white servants however, were commonly used as Live-In domestic labor. These servants were typically young women from Ages 13-30. Although many Black women worked as domestic labor, they often washed laundry or cooked for White families while living at home. Black Men who worked in the service industry at this time were often employed by hotels or as day laborers. Many Black service workers living on Hempstead street during this time, particularly those who lived in Savillion Haley’s “Hempstead Houses”, were migrants who were likely enslaved at birth. William and Hermanda Wesley who lived at 77 Hempstead, for example, were both born in Virginia during the 1840s.

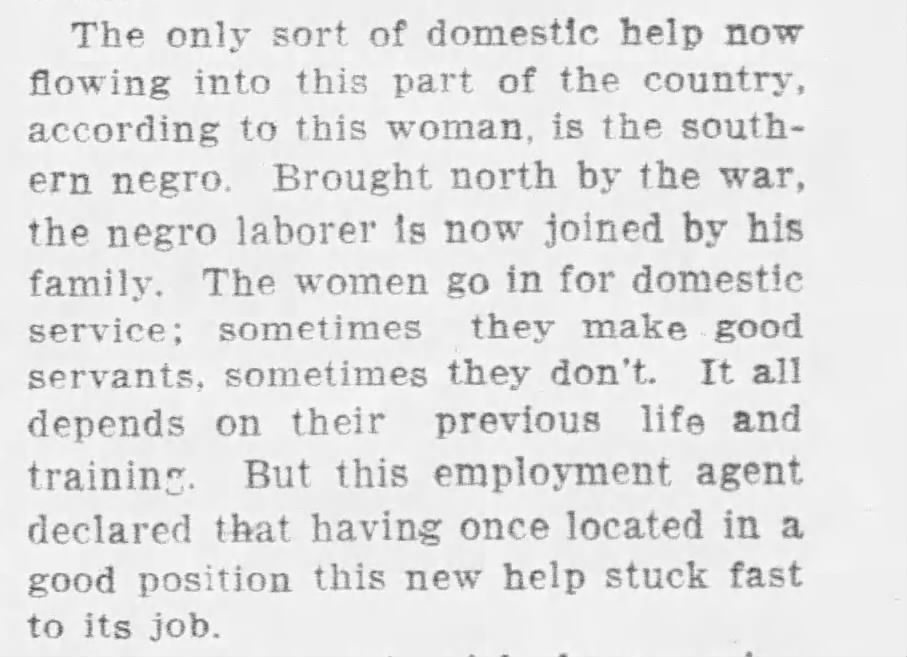

The above newspaper clippings demonstrate the shift towards Black domestic servitude in New London during the first decades of the twentieth century. Racist attitudes about Black women in service positions, including their supposed innate ability to withstand the cruel conditions of domestic Labor accompanied this shift. (Left) The Day, May 5th, 1916 (Right) The Day, October 14th, 1920

By 1920, some White homes such as those at 154, 190 and 236 Hempstead Street had transitioned from Irish to Black servants. These women were typically slightly older than their Irish counterparts, but there were exceptions such as Sylviana Tolver, a 14 year old servant living at 236 Hempstead. Many other Black women continued to work at home as laundresses. Many Black men seized new Job opportunities stemming from wartime needs, including positions at Naval bases as Janitors, and at docks as stevedores. Others continued working in hotels, and as day laborers without steady employment.

The Day, November 30th, 1928

By 1930, the Majority of employed Black women on Hempstead street continued to work in domestic service positions. White families still employed both Black and ethnic white live-in servants, but these women tended to be much older than servants in previous decades. Some Black women, like Leala Randolph who lived at 63 Hempstead, found work outside the home as a Hospital maid.

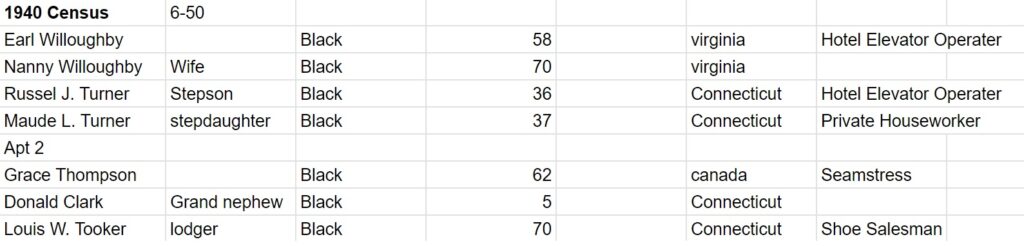

By 1940, live-in servants were becoming less popular on Hempstead street. Those that remain at this time have typically been working in the same homes for decades. A growing number of homes list older women in the family as dedicated Housekeepers. Young Ethnic White women began working in factories rather than in domestic labor. While many Black women continued working as laundresses, some entered into sales positions or factory jobs. 65 Hempstead Street in 1940 illustrates a building which housed tenants in both the industrial and residential spheres.

By 1950, there were no live-in domestic servants on Hempstead street. Black women who performed domestic labor largely worked as laundresses, or at hospitals and colleges. Young Ethnic White women who previously filled domestic positions worked mainly in retail, or as secretaries, stenographers or students. Black men worked mainly in manufacturing, or continued working in service positions such as hotel waiters.