In order to understand the vibrant community that emerged in New London over the course of the first half of the 20th century, we need to turn to the longer story of race, slavery and freedom in New England: a story that begins in the imperial world of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Taylor Desloge

Although a small city of less than 30,000 people today, New London offers an unusually rich history that challenges popular assumptions about the place of New England in American and African American life. Part of this history, after 1950, has been skillfully examined by Professor Anna Vallye and her students. Vallye has conducted an extensive exploration of New London’s place in America’s massive program of post-war urban renewal, which put millions of federal dollars behind the clearance of some 404,000 buildings, 40,000 acres and 300,000+ people in over 1,200 American cities. New London’s aggressive urban renewal program became part of a broader process of racial and class segregation, leading to the dislocation and dispossession of a large portion of the city’s working class population. This campaign of urban reconstruction and dispossession continued, albeit in a new garb, well into the 21st century. In 2005, the city of New London was thrust into the national spotlight again when the New London Development Corporation targeted the working class Fort Trumbull neighborhood for clearance, leading to the (in)famous supreme court case Kelo v. New London.

Nonetheless, the story that both Vallye and this site tell are chapters in a larger drama that begins in the imperial world of the 17th and 18th centuries.

From its founding in 1649, New London was enmeshed in the networks of trade and exchange that historians have long referred to as the Atlantic World. On July 17, 1761, the schooner Speedwell arrived in New London Harbor bearing some 74 surviving African captives out of 95 who had disembarked from West Africa. Some of the captives were directly sold in New London, where a local newspaper, the New-London Summary, advertised “To be sold, a Negro Wench just arrived from the coast of Africa.” (Anne Farrow, The Logbooks, 82).

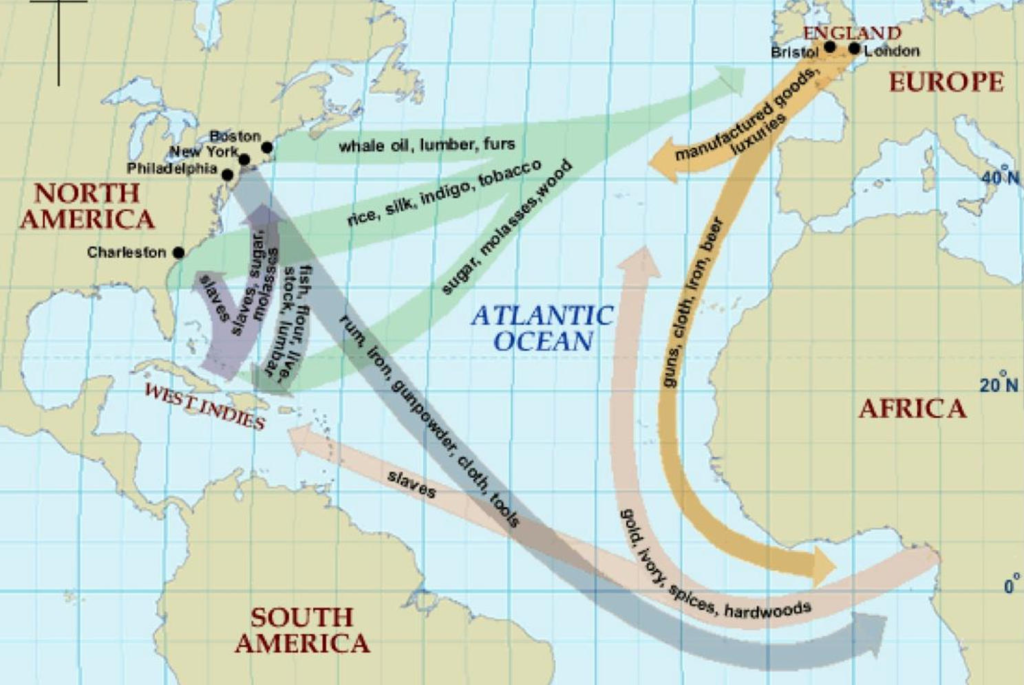

The Speedwell was the only ship known to have arrived directly in New London from West Africa bearing enslaved captives. Nonetheless, while New Englanders often like to imagine a certain ideological and physical distance from slavery, from its earliest days, historian Bernard Bailyn argues, slavery was the “key dynamic force” that propelled the region’s growth and prosperity (qtd. in Farrow, The Logbooks, 82). New London, widely considered the best deep water harbor on the Long Island Sound, was an important conduit through which New England’s markets, capital and goods gained access to the broader Atlantic world. In the 17th and 18th centuries, European planters were increasingly focused on the lucrative monoculture of sugar cane cultivation in the Caribbean. Sugar, first introduced in the Americas by the Portuguese in the 1550s, was the great cash crop of the 17th century–eventually eclipsing tobacco–and its expansion was intimately linked to the growth and maturation of New World slave societies. Sugar production was labor intensive. The sugar islands of the Caribbean–places like Jamaica, Barbados, Cuba, Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, Martinique–collectively received 47% of the estimated 12.5 million captives forced to undergo the Middle Passage between Africa and the Americas between the 16th and the 19th centuries. The average sugar plantation in the late 17th century contained sixty enslaved workers. By the 19th century, some plantations in Jamaica had grown to as many as 250 enslaved people. (Mary Draper, “Timbering and Turtling: The Maritime Hinterlands of Early Modern British Caribbean Cities,” 2017)

As planters invested in sugar and associated products like rum and molasses, they neglected the production of even basic staples. Consequently, New England became the breadbasket for the slave societies of the Caribbean. New London local historian Tom Schuch paints a dark picture of the city’s complicity, “New England and New London’s farms, fisheries and forests were the enablers and the provisioners of the Caribbean gulags.” Some 6,000-8,000 horses alone were shipped from all over New England to New London in the 18th century, where they joined cows, sheep, onions, barrels of salted fish and other staples on the southward journey to the sugar plantations of the Caribbean. “This became a very lucrative business for the people in New England, as well as for the planters — all at the expense of the kidnapped Africans who were enslaved and dying there,” Schuch adds. (Emilia Otte, “New London to Mark the Arrival of Slave Ship on July 17 at Amistad Pier,” Connecticut Examiner, July 22, 2022).

New London, in turn, offered a lucrative market for the slave-produced goods of the Caribbean. On any given day at the docks in New London, one might find sugar, spices and refined molasses direct from the Caribbean. As historian Anne Farrow notes, “The names of the local ships headed for and returning from the West Indies are listed in each week’s editions [of the local papers].” Alongside them one might find advertisements for slave sales, runaway slaves and all the goods of the Atlantic World (Anne Farrow, The Logbooks, 82).

New Englanders not only provided the staples that helped equip the Caribbean slave societies but engaged in the slave trade as investors and participants as well. New London provided, as Farrow writes, the “seasoned mariners, skilled shipbuilders and eager entrepreneurs” that made the slave trade possible. Her careful reading of Captain’s logbooks show New London men eagerly engaged in the buying, selling and transports of enslaved people. The Saltonsall family, wealthy merchants and descendants of New London founder John Winthrop, were notorious slavers. Dudley Saltonsall, who would one day serve as a captain in the Revolutionary War, was collectively responsible for the legal capture of over 63,000 enslaved people from Africa over between 1751 and 1777. Merchants Samuel Willis and Samuel Starr, provisioners of ships that plied the waters between New England, the West Indies and Africa, took enslaved people as payment for the settlement of their bills in the 1760s and 70s (Farrow, The Logbooks, 83). Samuel Gould ran a slave trading business from New London in the 1750s, and kept a book–now available at the Connecticut State Library–that recorded three voyages to West Africa from New London for the purpose of securing captives to sell in the New World. His books record the deadly toll of the Middle Passage, frequently noting deaths of enslaved people from diseases like dysentery. (Log Book of Slave Traders Between New London and Africa, 1757-58). Local historian Tom Schuch has found records of up to 40 ships based out of New London that traded in slaves in from the 18th century through the American Civil War. (Emilia Otte, “New London to Mark the Arrival of Slave Ship on July 17 at Amistad Pier,” Connecticut Examiner, July 22, 2022).

Marks of New England and New London’s complicity in the slave trade and the slave societies of the South and Caribbean remained strong until well into the 19th century. A journey through New London’s Cedar Grove cemetery in June of 2023 uncovered one such link. Gustavus W. Smith, a Major General of the Confederate Army, was laid to rest there in 1896. Born in Kentucky in 1821, Smith was a career Army officer and West Point graduate, having fought in the Mexican American War. In 1861, in spite of his home state of Kentucky staying in the Union, Smith enlisted in the Confederate Army and even, at one point in 1862, briefly commanded the Army of Northern Virginia. His wife was a New London native: Lucretia Bassett, the daughter of a prominent whaling merchant. She spent at least part of the war in New London taking care of her ailing mother, one of many New Englanders who formed ties–marital, financial or otherwise–with the slave south. (Carol Somer, “Love Of Country,” 2019)

Slavery in New London: Part of the Social Contract

Of course, New Londoners did not have to travel to the West Indies or the American South to see and experience the institution of slavery: many of them were enslaved themselves. Connecticut, while often counted among the “Free States,” had a slave culture of its own. At the time of the American Revolution, some 5,100 enslaved people lived in Connecticut. In New London, some one in ten residents were either of African or indigenous origin. The vast majority of those residents were enslaved as late as 1774, when New London County was home to as many as 2,036 enslaved people. Slavery was an integral, and for the most part, unquestioned, part of daily life in colonial New London. As a group of historians found in a recent study of the institution in the North, “In 1790 most prosperous merchants in Connecticut owned at least one slave, as did 50 percent of the ministers.” New Englanders not only tolerated slavery but “our economic links to slavery were deeply entwined with our religious, political, and educational institutions. Slavery was part of the social contract in Connecticut.” Frances Manwaring Caulkins, a 19th century New Londoner who wrote one of the first histories of the city, underscored the relative ubiquity of slavery in New London through her frequent mentions of the “servants” wealthy New London families kept in their households. In the early 18th century, “many families in town owned slaves” Caulkins wrote, “some but one; others two or three; very few more than four.” (Anne Farrow, Joel Lang and Jennifer Frank, Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged and Profited From Slavery, New York: Ballantine Books, 2005, xvii).

Some of our earliest accounts of captivity come, in fact, from the first hand perspectives of enslaved people in New England. Take, for instance, the story of Venture Smith (1729-1805). Smith, born “Broteer,” was kidnapped from present-day Ghana at the age of just six in the 1730s and sold into slavery in Rhode Island. For two decades he was enslaved on the 3,000-Acre sheep and dairy farm of George Mumford–who himself rented the property from the Winthrop Family–at Fisher’s Island, New York. After an escape attempt in 1752, he was sold to a farmer in Stonington, CT who promised to allow him to purchase freedom for himself and his wife, Meg. Ultimately, Smith was betrayed and, after being sold away once again to another Stonington merchant, was finally allowed to purchase his own freedom. Smith eventually became a prosperous farmer, building a homestead on Barn Island. In 1798 he published his autobiography, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, A Native of Africa: But Resident Above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself.” The narrative would be among the earliest of what eventually became a major genre of 19th century literature: the captivity narrative. (Venture Smith Freedom Site)

Slavery was so deeply intertwined in Connecticut society that New Londoners often had little patience for the presence of free people of color in their midst. In 1717, a town meeting was held in New London in which free people of color and “mulattos” were officially barred from the right to own land in the city. As Madison Taylor writes in her study of Black Mutual Aid in New London, “the provisions were retroactive, meaning if any free Black person had managed to buy land or own a business, their ownership was void and they would be subject to prosecution.” In 1719, in a chilling foreshadowing of the racialized displacement of the 20th century, one man, Robert Jacklin, a free Black man who had long lived in New London, was forcibly expelled from the city and forced to sell his home. (Madison Taylor, “Meeting Unmet Needs,” 7-8.)

Consequently, it is perhaps not a surprise that slavery died a relatively slow death in Connecticut, even compared to the other “Free States” of the North that enacted gradual abolition laws beginning around the time of the Revolution. Although Connecticut passed a gradual abolition statute in 1784, freeing any enslaved person born after 1784 upon reaching his or her 25th birthday, the process proved to be so extended that slavery as an institution effectively still existed in Connecticut until as late as 1848, when the last enslaved people were freed. Connecticut’s tolerance for slavery was one of the reasons why the slave ship Amistad was towed to New London upon its capture by the US Navy in 1839. Neighboring New York had abolished the institution by 1827.

Evidence of the lives and toils of enslaved people is omnipresent in New London today and offer crucial context for the story of Hempstead Street’s African American community. One can trace them step-by-step by taking a walking tour of New London’s Black Heritage trail. This is precisely what Professor Taylor Desloge, Sydney Marenburg (’24) and Eli Prybyla (’24) did in the Summer of 2023 as part of our research for this project.

New London’s Ancient Burial Ground, a 17th and 18th century colonial cemetery in the heart of the city, contains the final resting place of a number of enslaved people and their families including “Hercules, Governor of the Negroes,” a celebrated leader of New London’s colonial African American population.

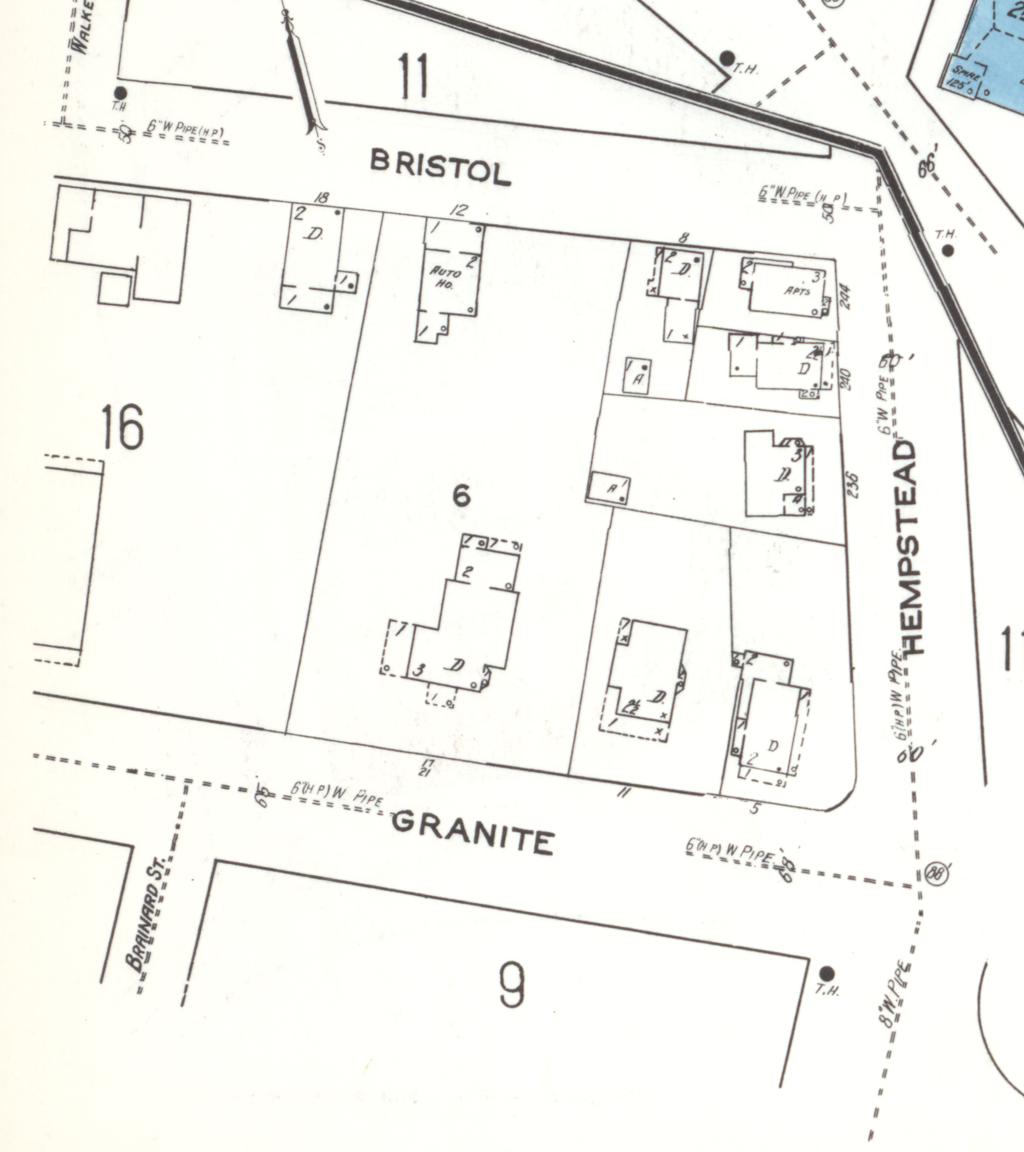

The connections to the Atlantic world established in the colonial era are likewise persistent well into the 20th century among the people of Hempstead Street. Among New London’s African American population were not just growing numbers of Southerners and New England natives but a population with deep connections to the Caribbean. For instance, 73-year old Bermuda Native Rosa Stowe kept the boarding house at 73 Hempstead in 1930, at the very moment the Hempstead Cottages were at the center of a web of institutions and properties then welcoming new Black migrants to the city.