During the Red Summer of 1919, New London experienced several episodes of Racial violence alongside cities nationwide. The city’s unique combination of size, high density of military personnel and a rapidly growing, socially organized Black middle class contributed to the racial anxiety which fueled violent ambitions of white rioters (Taylor 52). The first incident, an attack on the Hotel Bristol located on 92 Bank Street is emblematic of the reactionary attitudes present in racial violence.

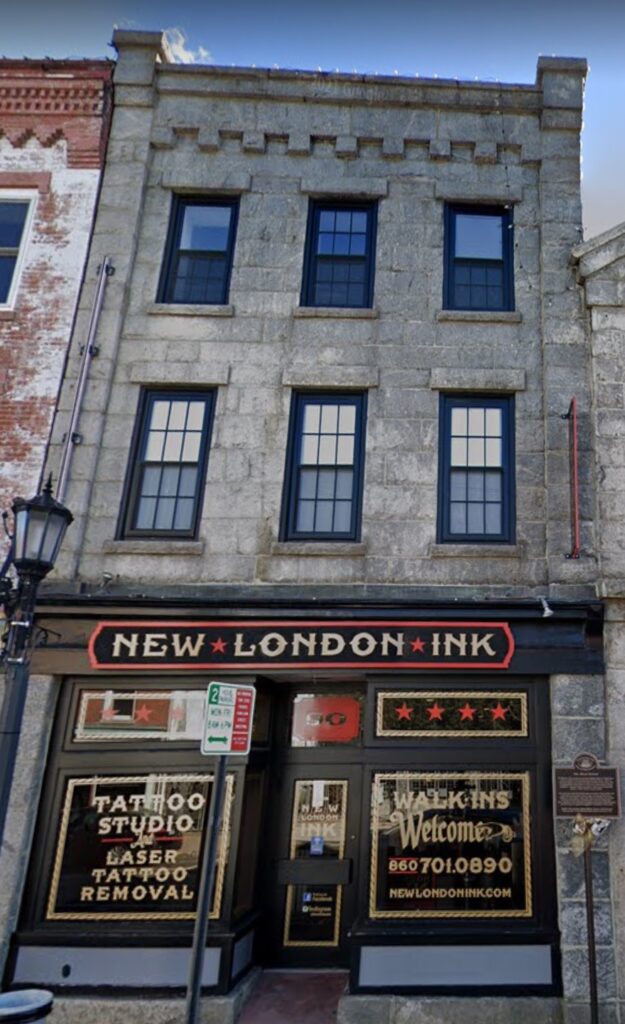

The Hotel Bristol Marker along New London’s Black Heritage Trail. Photographed By Michael Herrick, February 16, 2023.

The Hotel Bristol, which is listed in city directories from 1913 to 1920, was a short-lived yet culturally significant business for New London county’s Black communities. The hotel offered a venue for Black leisure in the heart of New London’s downtown, particularly for Black Sailors returning from Europe. Little remains in the historical record of The Proprietor, a Black man named James Nelson Reed, who was born in New York in 1860. Reed’s place of burial is known however, alongside his business partner and wife Addie in a Jeptha Lodge plot. The local Jeptha lodge #11 was a crucial social and philanthropic institution serving New London’s Black community (Schuch 2021). In 1914, The lodge leased space in 66 Hempstead street, a longtime home of Black community life in New London, and remained there for decades.

Reed’s presence in the Jeptha Lodge indicates that the Hotel Bristol was one aspect of a large concerted effort by New London’s Black community to achieve first class citizenship and economic stability in the early twentieth century. The targeting of the Hotel served to punish Black citizens for their recent and unwelcome presence in the heart of New London.

The Hotel Bristol’s association with Black fraternal organizations is important considering that Bank Street served as New London’s hub of White Fraternal organizations. Several lodges which did not allow Black members met regularly at 205 Bank street, just down the road from the Hotel Bristol.

The assault on the Hotel Bristol occurred on May 29th, 1919, after two White sailors who had been arrested earlier that evening convinced their associates that Black sailors had ambushed them. The resulting riot mob grew to five thousand, and surrounded the hotel, trapping and beating any Black visitors or workers they could (Braxton II 2021). Eventually, the assistance of the U.S. marines was required to end the immediate violence.

The Hotel Bristol was located at 92 Bank street, on the second floor of the building shown above

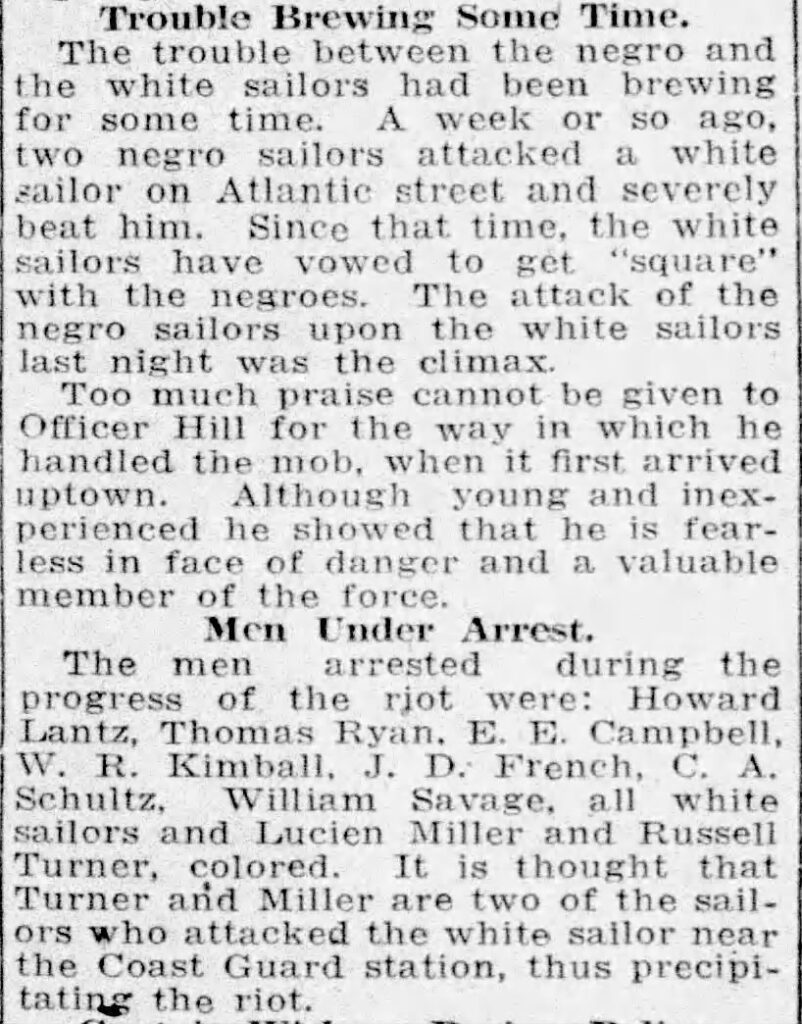

In the aftermath of May 29th, newspaper reports focused on white accounts of the attack which positioned Black men as violent instigators. A narrative of Black aggression remained popular in White newspapers, and became codified in the historical record (Taylor 56). Eventually, the narrative became so warped that Black men were thought of as having attacked the Coast Guard Academy directly. The repetition of this simple narrative is largely responsible for the lack of depth available for researchers to explore in written records.

The Day, 30 May 1919

After the attack on the Hotel Bristol, two more recorded episodes of Racial violence occurred in quick succession. On June 5th, two white police officers on Bank street attempted to arrest John Lightbecker and Jerry Beecher, two Black sailors who met to give non-alcoholic wet goods to a larger group of Black sailors. After a failed arrest attempt, the group of Black sailors demanded the bag be returned, as it did not contain alcohol like the officers suspected (Taylor 61). Later in the evening, Lightbecker and Beecher were arrested and police encountered the group of Black sailors, who they soon decided to arrest. Black sailors linked arms in an act of resistance against police injustice, and police began to use violence and the brandishing of a revolver to quell the demonstration.

On June 29th, one month after the Attack on the Hotel Bristol, a poorly recorded riot occurred near Fort Trumbull. This resulted in a broken fire hydrant and an ensuing liability debate, which created the only paper trail for this episode of racial violence.

It is unknown how many other physical attacks on Black life occurred during the summer of 1919 or beyond. It is likely that smaller attacks may have been skimmed over by Newspapers entirely.

Although the written record lacks sufficient material to fully understand the extent of racial violence during the summer of 1919, the threat of continued violence hung over the heads of New London’s residents. White instigators continued to see Black middle class life as incompatible with their vision of New London. Many Black New Londoners continued to organize and push toward economic and social citizenship. White Liberals, such as those involved in Connecticut College’s Service League, saw racial violence as the result of unresolved tension between Black and White people, rather than as the result of white supremacy and racial capitalism.

Bessie Wessel, of the sociology department, announced a new college sponsored initiative to encourage deeper inter-racial understanding shortly after the Attack on the Hotel Bristol. At a time when only white students attended Connecticut College, the initiative offered a well-paid learning opportunity which relied on the assumption that a patient and well meaning white person could create a breakthrough in inter-racial affairs.

Connecticut College News Vol. 4 No. 24